THERE ARE FEW PEOPLE in whom the sense of wonder is quick and joyous after the early childhood years have passed, and even many children nowadays seem to have it left out of them. One sees so many smug-faced little boys and girls whose calm eyes take everything for granted, to whom everything is a matter of fact.

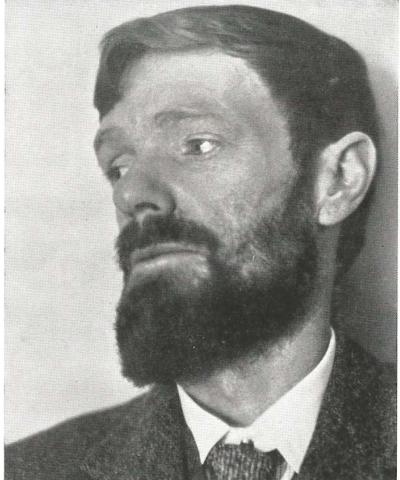

D.H. Lawrence will live forever in the memories of those who knew him and walked with him, who, with him beside them, watched the clouds cross over the mountains, or looked down into the hazy valley and saw the sunlight move across the gray desert land. For he was always aware of the miraculous significances. He seemed to be conscious of the meaning beneath the appearances in nature and in people, and the beauty and the terror of life that he perceived communicated itself to whomever he was with, so they too became aware of a deeper, more intrinsic, more startling reality than they were accustomed to.

He seemed able to perceive the essence of things, for it was as though everything was revealed to him, the truth under the camouflage, the actuality behind the veil; and he had the quickest sympathy, so it was possible for him to identify himself with other natures and beings than his own and know them to the core. He was often accused of being critical and negative where people were concerned but that was inevitable. He could not help it if he was able to read the thoughts and the feelings and motives that were masked, for others, beneath the gay facades in the bright personae of the world.

"D.H. Lawrence"

I do not believe he often judged or blamed people for what life had made them into, but frequently he did not like them and could not stomach the pitiful distortions of the original design. Certainly it was pleasanter for him to penetrate the serene mystery of a pine tree than the tormented mystery of almost any friend of his, and that he preferred the society of Susan, his cow, or his little black dog Pips, is not surprising.

He loved to go deep down into the secret life in the grassy hillside, to become a part of the smooth, delicate stream of unimpeded being in the wild orchids or the plum blossoms. And he was alive to all the sounds and odors and flavors of life so that when he drank his tea he really tasted it, and when he ate his hot scone he knew it was good. Or not so good! Washing his shirts in a tub of hot water out in the sunshine on the porch, he was conscious of the soft feel of the mountain water and the clean, hard smell of soap.

He always knew what he was doing. And this quick life in him quickened the dulled or oblivious life in others when they were near him and made them conscious, too, awakened them to small, real experiences that usually they did not notice, so that ordinary things took on a sharp, sweet aspect and became wonderful to them.

For Lawrence was a conductor of life. Some people neutralize life, block it and obstruct it for themselves, and for those near them. Lawrence brightened the room he was in, made it vibrate, made the surrounding air more iridescent, so everything grew meaningful and stimulating, and people, the dullest and most numb of them, responded to this involuntary touch of his. They woke up, they lightened, they began to be human. But there was no moral or ethical character in Lawrence’s miraculous influence. It was moral like the élan vital, it was like the wind that bloweth where it listeth, it was a creative, enhancing, and challenging force that as like as not stimulated to anger, anyway to some living emotion.

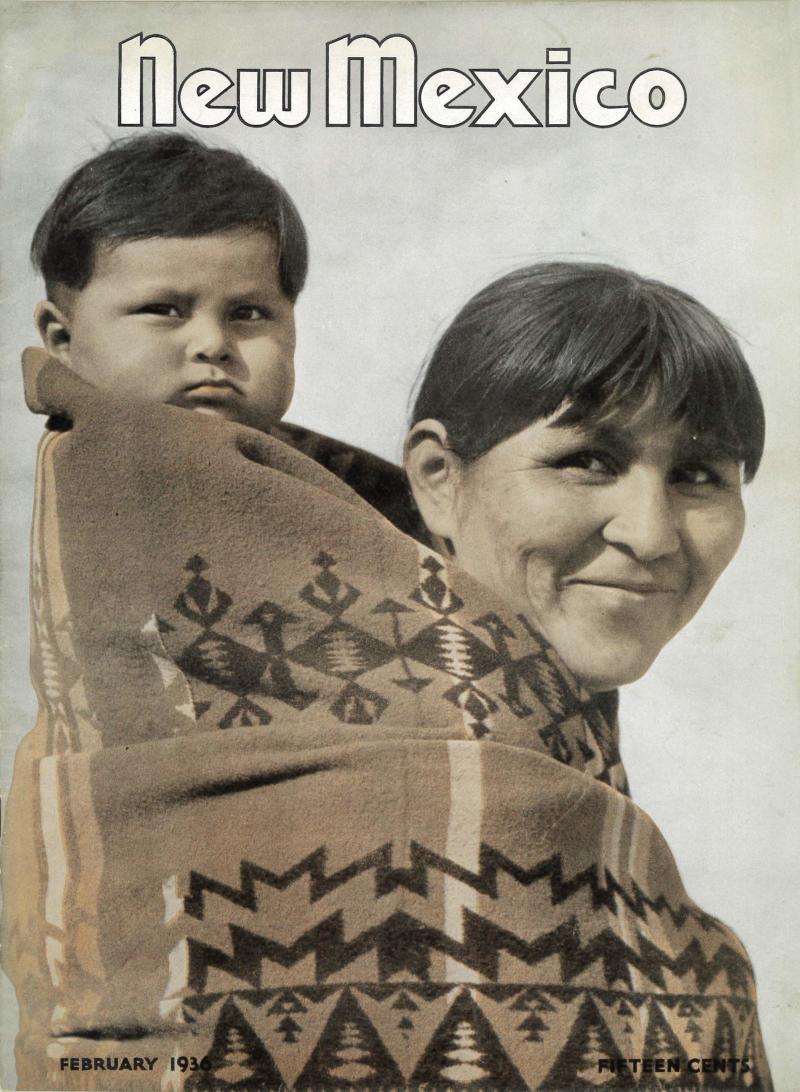

FEBRUARY 1936

NEW MEXICO MAGAZINE COVER

Nobody went to sleep when Lawrence was around! Nobody sank down into themselves and disappeared in the schizophrenic void! Oh no! His presence was a summons, a contact with the unavoidable. People would become more essentially themselves in his company, nicer or not so nice!

His heat brought out the invisible writing of human nature so that faces were more easily deciphered. It was strange how revealing a touchstone he could be, making things plain, too plain, sometimes! He was the friend of all natural life, the adorer of simple, true things and he was the enemy of everything mechanical, believing that machinery diminished life instead of saving it. It gave him a headache to ride in an automobile whirling him too implacably past through the tender countryside, and I am sure nothing would have persuaded him to use a washing machine.

Read more: North of Santa Fe, a water mill continues a tradition and brings a community together.

“I like to wash my shirt,” he used to say, and he never touched a typewriter, preferring to sit out under a tree and elan against its trunk to write on his knees, the small, neat, untroubled pages that flowed off his ancient fountain pen.

Of all places where he lived I know he loved Taos best for did he not tell me so, and write it many times, too, when he was far away? How he longed to come back here, and had he been able, perhaps he could be alive today.

He called this country “pristine” and no other word describes it so well. There was a quality in the air, in the spirit of the place, that was more congenial to him than any he ever found in Europe, Asia, or Australia, and it is a strange thing that this genius loci that he loved has as much the same effect upon individuals who come here that Lawrence’s spirit had upon people? For it also awakens them, stimulates them, makes them more essential; it reveals their buried life, and shows them up; it excites them, making them realize the color, taste, sight or sound of unspoiled natural life, almost forgotten in cities. And sometimes it overwhelms them, causing the balance to be lost, when horror at their own ruin is at last perceived in the clear light of these high altitudes, and they realize they have come too late to such a happy land. I have seen Lawrence affect a man in this way, and I saw that man shudder and shrink away from himself and what had been done to him out there in the world before he stumbled into Taos.

No, there was no one like Lawrence before or since his brief years here: no one like him for making all things new. His genius lay in his capacity for being, a capacity so few people seem to have. To comfort oneself for the absence of him one tries to believe that perhaps he was a forerunner, the first sample of the type to come, of those who will defeat industrialism and the mechanization of life, and who will lead humanity back out of the impasse where it perishes now.

The following article on New Mexico by Lawrence was one of the really appreciative things that has been written about it.

He always felt its magic.

Read more: The first chile feature by New Mexico Magazine describes the evolution of the chile.