Note: This article first appeared in the March, 2012 issue of New Mexico Magazine.

Although I was only seven, I still remember the day my family moved to Carlsbad Caverns National Park from Tucson, Arizona. I recall walking to the playground to see if there were other kids around. Sure enough, there were. After a few minutes of feeling each other out, I had some new friends. Like me and my sister, Anne, they were the children of park rangers who lived in a small housing complex across from the park’s visitor center. My childhood in a National Park had begun.

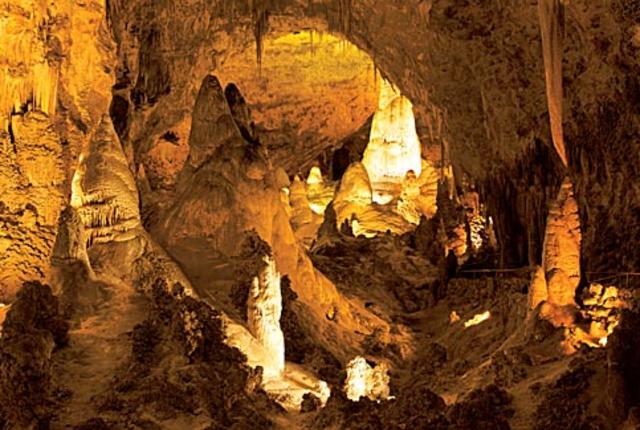

Before we settled into our new home, we visited Carlsbad Caverns. Downward we walked, our parents holding our hands, into the gaping maw of the natural entrance. As we descended, daylight faded, the air cooled, and its damp, earthy smell filled our nostrils. Mystery lurked in the shadows of the enormous underground chambers. The faint drip of water and the murmurs of other visitors were the only sounds. At Iceberg Rock, the ranger guiding our tour turned off the lights; the complete darkness became almost tangible. My sister and I scooted closer to our parents on the stone bench. The vastness of the Big Room, where people across the football field–sized chamber looked like tiny toys, amazed us. And at the end of our trip, the Underground Lunchroom in the Big Room offered up welcome snacks.

Our parents loved the park for raising children. Everyone knew everyone, so the parents looked out for each other’s kids. Other than the occasional rattlesnake, no one worried about anything bad happening. The park’s distance from town made going to movies, shopping, church, and extracurricular activities difficult. So we turned to the outdoors all around us for entertainment. My father and mother took us hiking on weekends in the backcountry. When we camped, Cloudcroft’s lush forest, cool summer temperatures, and proximity made it a favorite destination. During these excursions my father was guide, protector, and teacher: He calmed my sister and me one night when a bear prowled around our campsite. He showed us how to find fossil shells in limestone outcrops, and identified the towering conifers.

As my friends and I grew older, the park’s open spaces beckoned us farther afield. We would frequently hike a half-mile down to Oak Spring, a shady oasis tucked into an arm of Walnut Canyon where several small springs fed oaks, maples, and other trees. In the park’s early years the spring had provided water to park visitors and employees, but as visitation and demand grew, a new system was put in place. The waterworks at Oak Spring fell into ruin, creating a perfect place for kids to battle each other by throwing handfuls of mescal-bean seeds from the cover of the old tanks and buildings.

We became expert at building forts using rocks and sotol stalks. In summers, we cleared out debris in the center of a large juniper bush that lay above the main cavern entrance, and hid out there during the evening as hundreds of thousands of Mexican freetail bats exited the cave for their nightly hunts.

As I entered my teenage years, one of my park buddies, Bob Morelli, and I began to go caving frequently. We went on off-trail trips in Carlsbad Caverns, Slaughter Canyon Cave, and Spider Cave. When I was 13, Charlie Peterson and some other rangers taught me how to rappel and ascend on ropes, a critical skill for going into vertical pits. I soon did my first vertical trip: the 100-foot rappel into Chimney Cave. Stepping off the lip over a black abyss was terrifying. Looking down, I saw two tiny headlamps moving in the dark chamber far below. I took a deep breath and pushed off into the void. Once I realized that the rope would hold me, I relaxed a tiny bit and slid to the bottom. I arrived, sweaty and shaky, to congratulations from the rangers.

Today, there are 117 known caves in the system, but then, caves still awaited discovery, as they do even now. My friend Bob and I decided it would be cool to find an unexplored cave to fit the Star Trek ethos of the time: “to boldly go where no man has gone before.” At first, our search near Chimney Cave resulted only in sweat, rock scrapes, and pokes from cactus spines. At one point, however, Bob was on a treacherous slope below me when he screamed, “I found something! Cold air is blowing out of a hole!”

I stumbled down the hill, oblivious to the spiny plants tearing at my clothes. Sure enough, cold air was blowing strongly out of an eight-inch hole in some rubble, a sure sign of a substantial cavern below. We dug frantically, dust caking our sweat-soaked bodies. We enlarged the hole enough to poke a head and flashlight into it. We could see a drop of unknown distance opening into a large chamber. Loosened rocks crashed ominously down the slope for what seemed a long time. Unsure of its depth and excited beyond belief, we ran back to the housing area, grabbed my father, and banged on the door of ranger Charlie Peterson’s house. Amused at the sight of two young teenage boys covered with dirt tripping over words to describe what they had found, he nevertheless grabbed his gear and returned with us to the cave. While my father took photos, Charlie squeezed through our enlarged hole and scrambled down what we discovered was an eight-foot drop to the top of a steep slope near the roof of a large chamber. With his help, we followed. Together we wandered around the cave. The thrill of knowing we were the first people ever to be there was indescribable.

Over the years, we continued to venture into the rugged backcountry to look for new caves. On one trip we crawled into a small cave, only to discover a resident mountain lion. (We exited hastily.)

My developing passion for photography kept drawing me outdoors. When cavers discovered a passage into the heart of Lechuguilla Cave at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, I was one of the first people to photograph the enormous cave system. In 1988, over the course of three grueling trips, I plumbed multiple pits, and crawled, traversed, scrambled, and walked miles to shoot the cave for New Mexico Magazine. One trip stretched to 25 hours. On another, oblivious to the outside conditions while in the protected cave, we exited into a frigid blizzard, and became hypothermic as we ascended the entrance-pit rope and walked the mile back to the truck in the dark.

My first book, Hiker’s Guide to New Mexico (now Hiking New Mexico), brought me back to my childhood roots of spending time in the outdoors. To research the book, I spent several months hiking and photographing National Park Service sites and other public lands across the state. On some trips, the beauty of the landscape was as memorable as the exertion it took to experience them. I did a memorable 18-mile loop hike in seven hours on a scorching June day at Bandelier National Monument, near Los Alamos. I walked past the lonely, tumbled-down Ancestral Puebloan ruins of Yapashi, silently observed the Stone Lions shrine, splashed the welcome cool water of Frijoles Creek onto my face and clothes at Upper Crossing, and arrived back at the visitor center sweaty, dehydrated, and exhausted.

With my heavy camera equipment on my back, I trudged through the dunes that the Alkali Flat Trail traverses at White Sands National Monument, near Alamogordo. Up and down, up and down, I crossed the sand ridges, photographing the abstract patterns of the dunes as the afternoon shadows slowly lengthened. I reached the far end of the loop trail at the edge of Alkali Flat, a vast white plain of gypsum void of plant life that stretches toward the distant San Andres Mountains. The evening was windless; no people or animals were in sight. No planes were flying in or out of Holloman Air Force Base. The silence was so intense that I could hear my blood roaring through my ears.

Although I didn’t become a park ranger like my dad, my profession is still intricately tied to the outdoors. It’s a love I’m now sharing with my own children. One of my seven-year-old twins, Jason, traveled with me on a recent photo trip to White Sands National Monument. When I could get him to cooperate, I took photos of him leaping off the dunes. When I couldn’t, he rolled in the sand while I photographed the stark dunes, sky, and distant mountains. We stayed until sunset, him playing and me photographing the slanting shadows and golden light. At the car I made him take off his shoes and some of his clothes off to shake out the sand. Later, at a restaurant in Alamogordo, he stuck a finger in his ear and brushed out still more sand.

Jason and his sister are now having the same type of experiences that I had as a child. We hike, camp, and hunt for geocaches. At Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, the idea that people had once lived in the stone dwellings tucked into the caves intrigued them, so they hammered the ranger with questions. They closely inspected the ancient corncobs found in the ruins and eagerly climbed the ladders—experiencing their own thrills of discovery, as I have so many times over the years.

Laurence Parent visits New Mexico several times a year to photograph and visit friends. His 41st book, Photographing Austin, San Antonio, and the Texas Hill Country, was published by Countryman Press.