WHEN I SCHEDULE A CLASS WITH Silver City’s Wild West Weaving, Hosana Eilert gets the measurement from the top of my hip to the floor, to decide where I belong. “We’ll put you on the front loom,” she says, before showing me why height matters. Eilert pedals the treadles as her belly rests against the breast beam. “Everything is for production,” the weaving instructor explains.

Today, at the Río Grande counter-balance floor loom, first brought to New Mexico from Spain in the 16th century, I’ll weave a Río Grande–style rug—a striped textile that is longer than it is wide. First, I must choose my colors.

Eilert points me toward yarn by J. & H. Clasgens Co., an Ohio-based wool mill that has supplied Chimayó weavers since 1903, then to her own handspun and naturally dyed yarns. I select skeins of gray and green. Eilert takes both to her madajera, a skein holder made with a broom handle, and drapes the gray yarn around it. She slides one spool—a roll made from cereal-box cardboard—over a rod attached to a sewing machine motor and hits the pedal, winding my background-color yarn around it.

At the loom, she demonstrates how stepping on the treadles opens the sheds that lift alternating sets of the front-to-back warp threads. She tells me to “make a mountain” with my finger to open the threads a little as I pass the spool between them, shift my feet to open the opposite shed, and repeat. Returning the spool to the starting side completes a round. A too-high mountain adds extra yarn and creates unwanted waves, while a short mountain makes the piece look threadbare. But Eilert doesn’t allow me to sweat any potential mistakes.

I continue making rounds while she spins yarn from what she calls “the last of her Churro,” wool sourced from descendants of the sheep Francisco Vázquez de Coronado introduced to New Mexico around 1540. We chat about the history of Chimayó–style weaving. “If you think of blankets in the Southwest, you’d think about Navajo, Río Grande, and Pueblo styles,” she says.

In Spanish colonial times, woven textiles were New Mexico’s chief export. Carried on by a few families—including the Trujillos, with whom Eilert apprenticed—the Chimayó style is dominated by diamond, hourglass, and rectangle shapes. The Río Grande weaving tradition, as a whole, progressed through multiple design styles: from the Spanish colonial Río Grande stripes to the Mexican Saltillo diamonds and the American-influenced Vallero stars with eight points, and then the Chimayó style, which developed after 1900 and traditionally features two stripes and a center design.

Read more: Hone your pottery skills at these hot spots around the state.

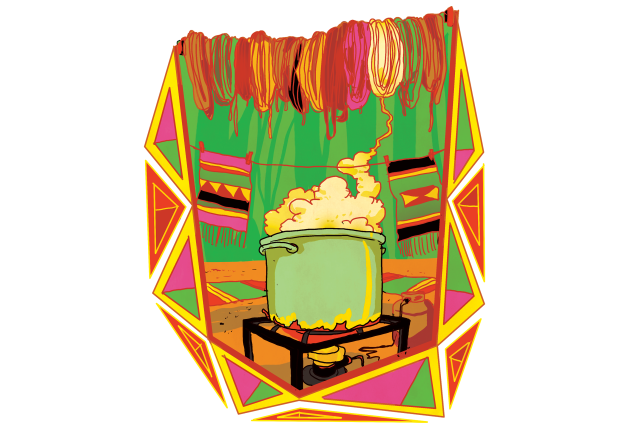

New Mexican fiber artists used handspun wool from their own flocks and had a range of natural colors, but eventually they used native dyes, and then imported ones. Today, many weavers have returned to the natural dyes—gold and brown hues from plants like chamisa, reds made from dried and ground cochineal bugs, blue tints from the indigo plant.

As I listen, I find my tempo. But I am also eager to advance. Eilert shows me how to add a new color by slipping the yarn end under three sets of threads and locking it in by switching sheds. She trims the ends closely with scissors. “I don’t let students do this part,” the teacher admits. She doesn’t want the warp threads snipped along with the yarn. “It takes a day to set up a walking loom.”

She instructs me to alternate colors for each round. Eventually, my mini rug is removed from the loom—one side’s threads hanging out—and weighted down with a hardback book. She gathers a few of the threads together and twists them into an overhand knot, snugged up against the last pass of yarn. While I tie the rest, Eilert weaves her own tale.

She grew up in northern New Mexico, where her parents played in a band with master Chimayó weavers Lisa and Irvin Trujillo. After working in their shop for a year and a half, she learned to weave at age 19. She didn’t start with stripes—her first rug included the many design elements that exemplify the complex Chimayó tapestries.

But Eilert knows that most people wanting to connect through weaving don’t need that kind of intensity. “Perfection is part of the tradition, though,” she says.

While examining my knots, I note aloud that I can tell which ones were tied by Eilert. She reminds me that we each have our own rhythm and that tassels are just one characteristic that make each tapestry special, differentiate artists, and add value to handcrafts. I study the intricacies of my own weaving, and understand how much more I have to learn.

Sign up for weaving lessons at wildwestweaving.com.